Calvin's Quincentenary: A Catholic Response

This summer marks the five hundredth anniversary of the birth of the Swiss Protestant John Calvin.

Calvin was an adequate theologian, whose statements on justification were found to accord well with the Catholic doctrine on the same point by several Vatican cardinals who conversed with him at the Regensburg Colloquy on the eve of the Council of Trent; he was an experimental politician, who attempted to adapt the Church's internal ordering and sacramental life to the civil sphere; as a family man and friend, he was a frequent failure. As an heir of the proposals of Martin Luther, Calvin manages to sidestep most accusations of outright schism, although the charity at work in his writings is scarce. And yet, as the Church's ecumenical documents remind us, grace was at work in his proposals; his stern commendation of local accountability, the careful study of Scripture, and his personal striving for holiness can resonate with the Church's life and even offer a breath of fresh air from the outside, in the same way that the fourth century schismatic Donatists, with all their rigor and care, probably offered a note of inspiration to the struggling Catholics of the earliest Church.

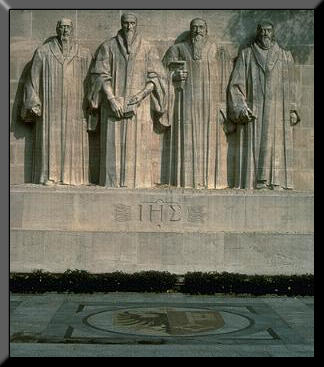

On the whole, Calvin's legacy is a shining one. I was in Geneva a few weeks ago, and I strolled with a friend by the long Reformation monument in the center of the lovely park which faces Lake Le'man. For all Calvin's denunciation of the so-called "doctrines of man," the monument seems to refer to little beyond a few men and the textual approach to the life of God which Calvin championed. Here there are no crosses, no images of the often illiterate sainted men and women who have born witness to Christ through their bodies, and whose lifeblood has provided the seed of the Church. There is instead a small cluster of fierce men, holding books, and a running script of the Lord's prayer cast in several elite ancient languages, all shining with the benefits of the education, industry, and prosperity which Calvin decided to associate with the faith of the wandering Nazarean. Everything was quiet around the shining monument, which stood very silent in the sunlight, as though it were waiting for something more.

It was a different sight that evening at Mass in the Geneva cathedral of Notre Dame. I was not prepared for what we saw there, but it was the eve of Pentecost, and the Holy Spirit is on the move, making one of the Father's scattered people. There were two hundred men, women, and children waiting outside the cathedral, all kinds, many dressed in white, standing in the dusty pavement. There were old and young, rich and poor. There were Swiss bankers and French families and dozens of couples from Africa. They were waiting to process into the Church, amid noise and laughter and voices and celebrating families; and in they came, not just for any Mass, but for their confirmation. Each and every one of two hundred adults professed their faith in all that the Catholic Church believes, teaches, and proclaims. And the Scripture was read and honored, as always, and the families were exhorted, and something more; while light streamed in through medieval stained glass windows, and the glorious strains of Palestrina filled the air, I worshipped there with saints and sinners, with illiterate children and homeless people who entered at the back (though they are probably the greatest in the kingdom of Heaven). Together we knew that we were in unbroken continuity with those who had sung to our Lord from the beginning. It was an imperfect fellowship that day, but Catholic fellowship it was in the fullest sense, with nothing left for which to wait on this side of Heaven. It was the fellowship which reaches around the globe and back in time to the will of the wandering Nazerean who is our Lord and God.

For all his shining legacy of a literate and carefully delineated approach to a revised doctrine, Calvin chose to overlook the fundamental tenant of all that his teacher Augustine held forth when he spoke to those of his own time who contemplated leaving the Catholic Church for what seemed to them like a purer ideal: "The spirit that is in you, oh man, and by which you are a man- does it then quicken any member that has been separated from your flesh? Your soul quickens only the members that are in your body; if you cut off any one of them it soon ceases to be quickened by your soul, since it no longer has any share in the unity of your body. I say these things that you should learn to love unity and fear separation. The Christian should fear nothing so much as separation from the Body of Christ." (Tractates on John 26.13)

For all his highly literate rigor, Calvin overlooked the more important thing- that Joy comes at the price of the obedience which preceeds understanding, of submission to authority, which lies at the heart of the law of the universe. It is the same logic which reminds us that though we have all wisdom and knowledge, and though we might have refined our faith such that we are ready to move mountains of cultural accretions, if we have not the love which can hold the most ancient fellowship in place, we will come to back only to ourselves, which is to come to nothing. And indeed, that coming to nothing which the enemy of our souls always intended continues to find its slow, steady work of demise in every fragile, well-intentioned community which has been cut off from the whole. Contemporary theologians who marvel at Calvin's resonance with Catholic doctrine note that the one point on which there could be no consensus was the matter of authority. Calvin's legacy is in the end not a legacy of a return to Scripture or of the adoration of Christ alone; those gifts were given to the Church in full long ago, and they were lived out by humbler saints for centuries. Even Calvinists are eager to point out that Calvin is merely the true offspring of 14th century Catholics such as St. Bernard of Clairvaux and his Cistercian brothers. What Calvin left to the world is a pattern of justifying one departure after another.

When I departed Geneva, I returned to the work which is defined by the wounds of our time; I returned to a local community in which abortion mills are presided over by good Presbyterians, and I returned to the news of the violent death of one particular church-going Lutheran who made his living by carving up little babies. The ongoing cycle of those who live by the sword continues, and a myriad voices chatter for attention, while our Lord simply waits in Calvin's quincentenary for His people to return and to be one, under the voice of one Shepherd, for all the world to see- just as He intended.

<< Home