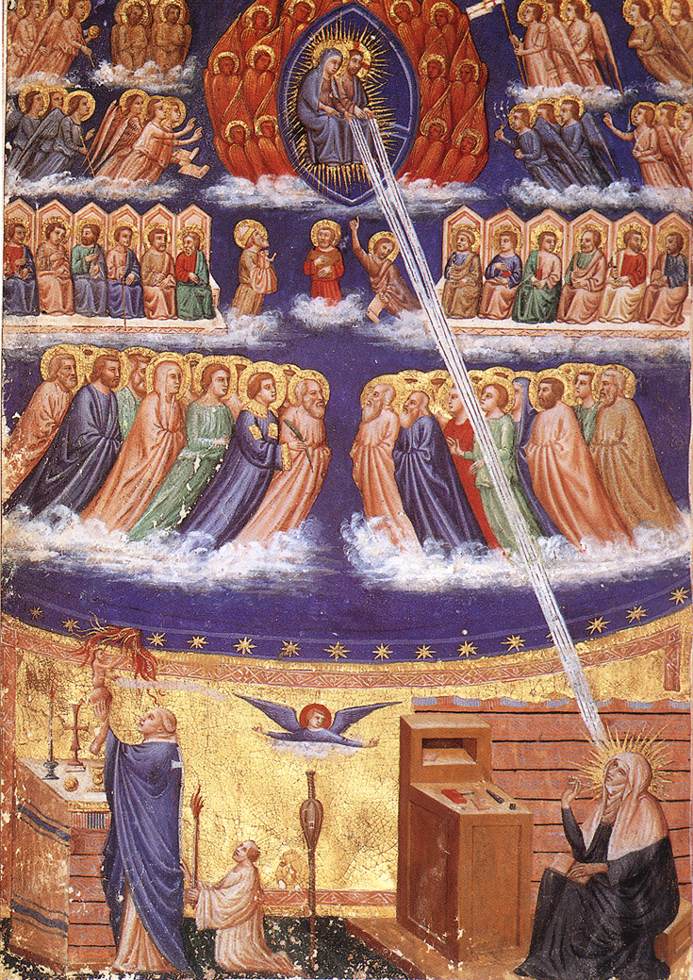

Today the Church asks that God shed "the rays of His grace" on those who have yet to believe in and extol His mercy.

One of the most consoling passages in Scripture for me is the assurance that the very heavens declare the glory of God, and their light has gone into all the world (Psalm 19); there is a light which has enlightened everyone (John 1). There is excellent support for this Biblical idea in the unassuming defense of the Christian faith that is offered in the most surprising corners.

For instance, it was the French sociologist

Emille Durkheim (1858-1917) who originally proposed the familiar refrain against our faith that

religion is humanity's created device, by which humanity can meet its needs by forming the community and society that it craves. Primal people want and need to be together; so they form various religions to provide a sense of social cohesion and moral responsibility. A sense of religion provokes communal consciousness and common emotions, which enhance a sense of group identity and establish the group itself as a worthy, 'sacred' reality. Furthermore, necessary societal expectations are framed and protected as the will of the gods. In reality however, it is the human community that is really "god," and it is the community- not a real divinity- which humanity ultimately "needs." In Durkheim's words, "

the sacred is nothing more nor less that the human society (with its authority and beneficence)

transfigured and personified." In another instance, Durkheim explains: "

Society determines, while religion is the thing determined. Society controls; religion reflects." The essence of Durkheim’s theory of religion is that society is the all-pervasive force from which religious beliefs have evolved.

It was

Mircea Eliade, the Romanian father of modern Religious Studies (1907-1986) who answered these reductionist claims by asserting that the religious experiences of human beings matter, and that on the evidence of the human experience of a personal and real God, theories such as Durkheim's become indefensible.

First, Eliade pointed out that

the religious longings of humanity tend to be universally the same, regardless of time and place, whereas social needs are transient and socially conditioned, and their solutions are widely diverse; thus it is the former reality of

the universal human sense of the sacred that points to something truly transcendent and real in human experience. In particular, the universal prevalence of mythic atoning savior tropes and myths of an eternal return

pointed to the Christian story as the best manifestation of the sacred.Secondly, Eliade reminded the world of the gross elitism of Durkheim's claims. Durkheim spoke as a Frenchman of the nineteenth century, for whom

everything was political. As such, he could not purport to speak truly for the millions of complex and spiritual human beings who had their own account of what religion really was, and knew for themselves what they meant by the

reality of the sacred.

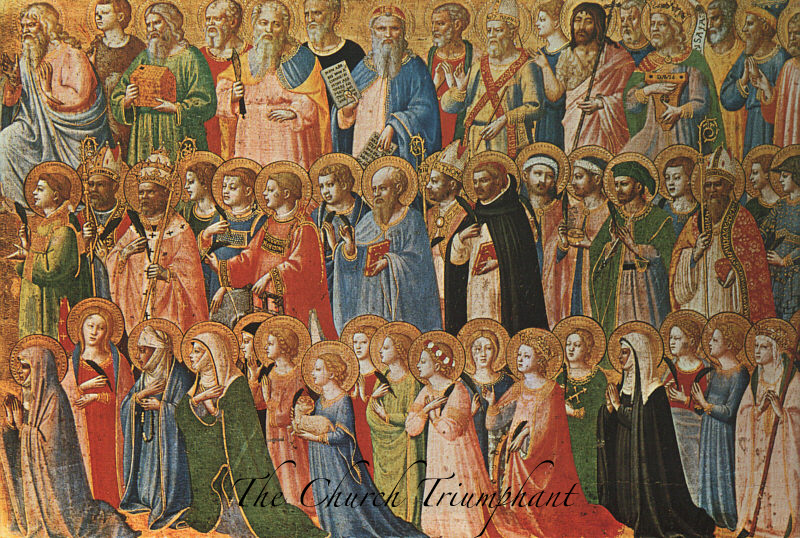

Eliade proposed that we actually listen to the claims of faithful people. Rather than imposing Western reductionist structures upon personal accounts of the sacred, Eliade held that a more authentic account of religion should be

derived from the stories of simple people who claimed to have encountered God.

In short, Eliade might democratically suggest, "how do you know there is a God? -

Listen to the people who worship Him."More on my hero Eliade here.