Living in Advent Hope: Wherever You Are, I Am

Because Advent is the season of living our hope as the celebration of holding, now, all that Christ has already accomplished for us, of having nothing that we have not received, of proclaiming the salvation already accomplished.

Augustine’s favorite popular descriptor of the Christian church, as we find in his sermons, is that of a virgin bride, contracted in marriage by the conflated covenantal/inheritance structure neatly summarized in the tabulae matrimoniales. The family law of the classical Julian age required laborious negotiations between the father of the bride and the prospective son- in- law, which ultimately designated their own covenantal exchange of goods (in bride price and dowry) that culminated in the body of the bride.

While the Roman law of St. Augustine’s time excluded the bride from the commercial negotiations in anticipation of her wedding, the law expectantly required the waiting bride to signify her public and free consent to the contract arranged between her betrothed husband and father. She showed her legal consent in multiple and recurring ways.

She would have worn her betrothed’s bronze rings, symbolizing the durability and frugality of the empire that her household would constitute. She would have clasped his hand publicly, face- to- face, in symbolic declaration of fidelity. And lastly, following even the ratification of the detailed deed of purchase by which she was bestowed upon her husband at his wedding, she had to pause one last time on the threshold of her husband’s home for her final and free public act of consent to his nuptial invitation, without which no legal marriage could take place. She said Quando Tu, Ego: whenever and wherever you are, I am then and I am there… wherever you are, I am.

I think it’s a fascinating statement, linguistically. Quando is a Latinate free-for-all. The word is a potential interrogative, carrying within it a multitude of ongoing questions: Who are you?... Where are you?... Who will you become? It’s also a relative adverb, conditioned by the data of times and places beyond control, relativized by a dozen possible particles that may alter its construal in grammatical structures. And the word is also a conjunction, situated tentatively in the immediate place between all that has gone before, on the one hand, and, on the other, the moment wherein the bride pauses for breath before her final statement.

The bride's response to this tentative, broadly contingent qualifier is so simple. For herself, she must speak with the starkest clarity of a unilateral promise that stands in relation to one contingency alone and none other. She alone seals the nuptial contract with the all-consuming self-reference of the singular being verb: I am.

Patristics scholar John Cavadini has suggested that the Fathers work in images as much as they do in concepts. They find in every image of bride and groom the vivid reality of Christ's espousal to His Church, for which human nuptials are merely the shadowy metaphor. The Fathers find the Church in Eve, in the valiant woman of Proverbs 31, in Ruth; the Church is the one who follows the Lamb wherever He goes, saying, as we have heard it before, where you dwell, I will dwell; your people shall be my people, and your God, my God. Augustine finds an image of the Church in every Roman bride who seals her matrimoniales with her vow upon her husband's threshold.

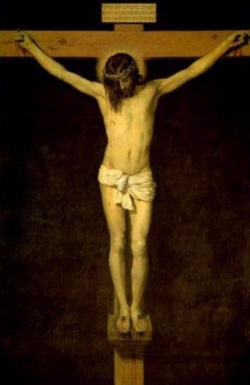

The far-out exegetes in my life remind us that in Scripture, the precise exchange above- where you go, I will go, the Old Testament equivalent of the Quando Tu- occurs between two women, not between a nuptial pair. But the reality is that in the Christian faith, this declaration is not so much spoken as it is finally enacted. It is the Bridegroom Himself who utters the final words of covenantal consummation. The final act of (divine) consent is completed in His own body: it is finished.

Just as Roman customary norms understood that the bride was formed into a true, mature personal agent by conformity to her husband, Augustine locates the formation of the Church as Christ’s nuptial body upon His Cross- In Christ's case, a bride was born for Him as He hung on the Cross, and the Church was made from his side. With a lance his side was struck as he hung there, and out flowed the sacraments of the Church. (Ennaratione 56.11).

The consenting, responsive ego has, of course, already been spoken. The Holy Spirit has already hovered over the first fruit of the Father’s promises to the Son, when a timid teenage girl in Nazareth paused at the threshold of her spouse’s household, and, to conclude the long series of free acts of assent made by the symbolic gestures of her ancestors, gave consent to the terms once established between the Father and the Son: may it be to me according to your word.

(Mary, of course, did not know about Roman jurisprudence. She does not speak with the merely self-referential ego of the contracted bride; she speaks with the determination of an adjudicator: Fiat. It is, after all, God who has proposed to her.)

To all who will join her first act of consent, so that with her definitive “let it be to me according to your word, wherever you go, I will go,” we simply join in: “Amen.” The door to the Father’s household has already been opened, the nuptial Covenant has been ratified, the Word has been made flesh in the body of a bride, the marriage has been consummated on the Cross, its procreative purpose is already unfolding in the weary world as we are gathered, more and more, into Christ’s embrace. Consumatum est. You know how the rest goes. It’s just a matter of time.

…But the bride no longer pauses on her husband’s threshold. It is now He who stands at the door and knocks: Quando tu, ego.

Augustine’s favorite popular descriptor of the Christian church, as we find in his sermons, is that of a virgin bride, contracted in marriage by the conflated covenantal/inheritance structure neatly summarized in the tabulae matrimoniales. The family law of the classical Julian age required laborious negotiations between the father of the bride and the prospective son- in- law, which ultimately designated their own covenantal exchange of goods (in bride price and dowry) that culminated in the body of the bride.

While the Roman law of St. Augustine’s time excluded the bride from the commercial negotiations in anticipation of her wedding, the law expectantly required the waiting bride to signify her public and free consent to the contract arranged between her betrothed husband and father. She showed her legal consent in multiple and recurring ways.

She would have worn her betrothed’s bronze rings, symbolizing the durability and frugality of the empire that her household would constitute. She would have clasped his hand publicly, face- to- face, in symbolic declaration of fidelity. And lastly, following even the ratification of the detailed deed of purchase by which she was bestowed upon her husband at his wedding, she had to pause one last time on the threshold of her husband’s home for her final and free public act of consent to his nuptial invitation, without which no legal marriage could take place. She said Quando Tu, Ego: whenever and wherever you are, I am then and I am there… wherever you are, I am.

I think it’s a fascinating statement, linguistically. Quando is a Latinate free-for-all. The word is a potential interrogative, carrying within it a multitude of ongoing questions: Who are you?... Where are you?... Who will you become? It’s also a relative adverb, conditioned by the data of times and places beyond control, relativized by a dozen possible particles that may alter its construal in grammatical structures. And the word is also a conjunction, situated tentatively in the immediate place between all that has gone before, on the one hand, and, on the other, the moment wherein the bride pauses for breath before her final statement.

The bride's response to this tentative, broadly contingent qualifier is so simple. For herself, she must speak with the starkest clarity of a unilateral promise that stands in relation to one contingency alone and none other. She alone seals the nuptial contract with the all-consuming self-reference of the singular being verb: I am.

Amen; the nuptial covenant is complete.

Patristics scholar John Cavadini has suggested that the Fathers work in images as much as they do in concepts. They find in every image of bride and groom the vivid reality of Christ's espousal to His Church, for which human nuptials are merely the shadowy metaphor. The Fathers find the Church in Eve, in the valiant woman of Proverbs 31, in Ruth; the Church is the one who follows the Lamb wherever He goes, saying, as we have heard it before, where you dwell, I will dwell; your people shall be my people, and your God, my God. Augustine finds an image of the Church in every Roman bride who seals her matrimoniales with her vow upon her husband's threshold.

The far-out exegetes in my life remind us that in Scripture, the precise exchange above- where you go, I will go, the Old Testament equivalent of the Quando Tu- occurs between two women, not between a nuptial pair. But the reality is that in the Christian faith, this declaration is not so much spoken as it is finally enacted. It is the Bridegroom Himself who utters the final words of covenantal consummation. The final act of (divine) consent is completed in His own body: it is finished.

Just as Roman customary norms understood that the bride was formed into a true, mature personal agent by conformity to her husband, Augustine locates the formation of the Church as Christ’s nuptial body upon His Cross- In Christ's case, a bride was born for Him as He hung on the Cross, and the Church was made from his side. With a lance his side was struck as he hung there, and out flowed the sacraments of the Church. (Ennaratione 56.11).

The consenting, responsive ego has, of course, already been spoken. The Holy Spirit has already hovered over the first fruit of the Father’s promises to the Son, when a timid teenage girl in Nazareth paused at the threshold of her spouse’s household, and, to conclude the long series of free acts of assent made by the symbolic gestures of her ancestors, gave consent to the terms once established between the Father and the Son: may it be to me according to your word.

(Mary, of course, did not know about Roman jurisprudence. She does not speak with the merely self-referential ego of the contracted bride; she speaks with the determination of an adjudicator: Fiat. It is, after all, God who has proposed to her.)

To all who will join her first act of consent, so that with her definitive “let it be to me according to your word, wherever you go, I will go,” we simply join in: “Amen.” The door to the Father’s household has already been opened, the nuptial Covenant has been ratified, the Word has been made flesh in the body of a bride, the marriage has been consummated on the Cross, its procreative purpose is already unfolding in the weary world as we are gathered, more and more, into Christ’s embrace. Consumatum est. You know how the rest goes. It’s just a matter of time.

…But the bride no longer pauses on her husband’s threshold. It is now He who stands at the door and knocks: Quando tu, ego.

<< Home